Basics of LCMS Systematic Troubleshooting

LCMS Troubleshooting Course

1 - Basics of LCMS Systematic Troubleshooting

2 - Preventive Maintenance Measures

3 - Pressure Issues

4 - No Peaks Detected

5 - Changes in Peak Shape - Part 1

6 - Changes in Peak Shape - Part 2

7 - Ghost Peaks

8 - Peak Area Fluctuations

9 - Baseline Disturbances

10 - Retention Time Fluctuations - Part 1

11 - Retention Time Fluctuations - Part 2

12 - Changes in Chromatographic Resolution

13 - Changes in MS Response

14 - Undesired Fragmentation & Ion Source Settings

15 - Course Summary & Quiz

Welcome!

Welcome to our Free Online Course: Troubleshooting in Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry!

We are excited to have you join us for this seven-week journey into the world of troubleshooting and preventing common errors in LCMS applications. Each week, you will receive an email with two or three informative topics designed to enhance your understanding and skills in mass spectrometry troubleshooting.

Our first week will establish the foundations of systematic troubleshooting, providing you with valuable general guidelines for preventing and avoiding common errors. It will also look at the basics of the mass spectrometer components.

Basics of Systematic Troubleshooting

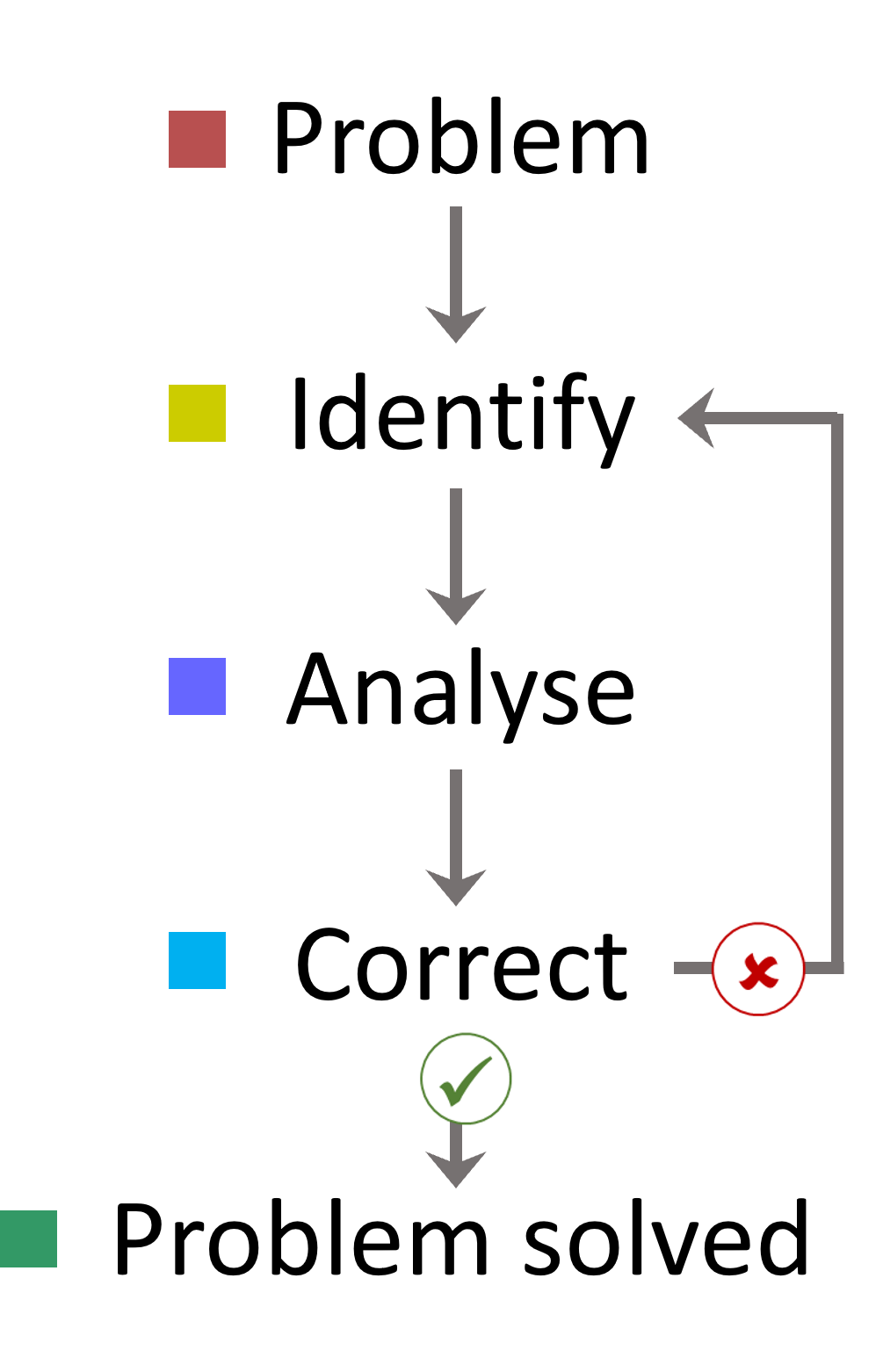

A systematic approach is crucial for effective troubleshooting and problem resolution. By approaching issues in a stepwise fashion, we can begin to understand the problem:

1. Narrow Down the Problem

- Focus on one potential issue at a time. This allows you to identify the cause more accurately.

2. Understand Your System

- Familiarise yourself with your LCMS and method / application. Key aspects to monitor include:

- Baseline of a blank measurement

- Pressure behaviour

- Retention time and peak area of analytes

- Peak shapes

- Tuning Results

Having consistency between runs - such as a standard you run with each batch or buying pre-mixed solvents - can help you track these parameters effectively.

3. Analyse and Resolve

- After identifying a problem, it's possible to understand and narrow down potential errors. In upcoming course topics, we will cover the most common issues and the changes that can be made to resolve the issue. If a change doesn't solve the problem, start from the beginning and test the next possible source of error. It is important to systematically change only one factor at a time to establish the cause of an error.

4. Document Your Findings

- Keep a record of the errors encountered and the changes made. This documentation benefits you and your colleagues by improving collective knowledge and speeding up future troubleshooting.

5. Dispose of Defective Parts

- When replacing aged components, if the issue has been resolved, dispose of the old / worn parts immediately to avoid reinstalling them later. If the replaced part hasn’t solved the issue then it could be worth keeping them for a later date. Keep them somewhere safe and labelled so colleagues know what they are.

Some of the most common sources of error which should be investigated first include:

- Electrical connections and power supply

- Communication between the instrument and the PC

- Standards and sample preparation

- Mobile phase preparation

- The analytical method conditions

- LC fittings, connections and flowpath

- Needle rinse and seal washes

- LC pump pressure and potential air bubbles

- Ion source maintenance and cleaning

- MS vacuum

- External generators and cylinder issues including Argon gas (level and pressure), gas generator (pressure readings) and roughing pump issues (oil level and gas ballast)

Only one variable should be changed at a time to logically identify trends and isolate possible causes. Everything should be documented, including retention times, normal LC pressure and samples injected. A system suitability test can provide vital performance information to assist with troubleshooting.

Structure of an LCMS

To be able to fully troubleshoot, we first need to understand the structure of a typical LCMS system. An LCMS is composed of two instruments – the liquid chromatograph system and the mass spectrometer.

Every HPLC is fundamentally built the same. It consists of a solvent delivery system, an injector, a separation column, a detector, and the solvent waste. Ideally, an online degasser and a column oven are installed to ensure reproducibility. These modules are covered in the HPLC Troubleshooting Course, which we encourage you to look through to learn how to eliminate common issues with the LC.

The mass spectrometer is composed of three components:

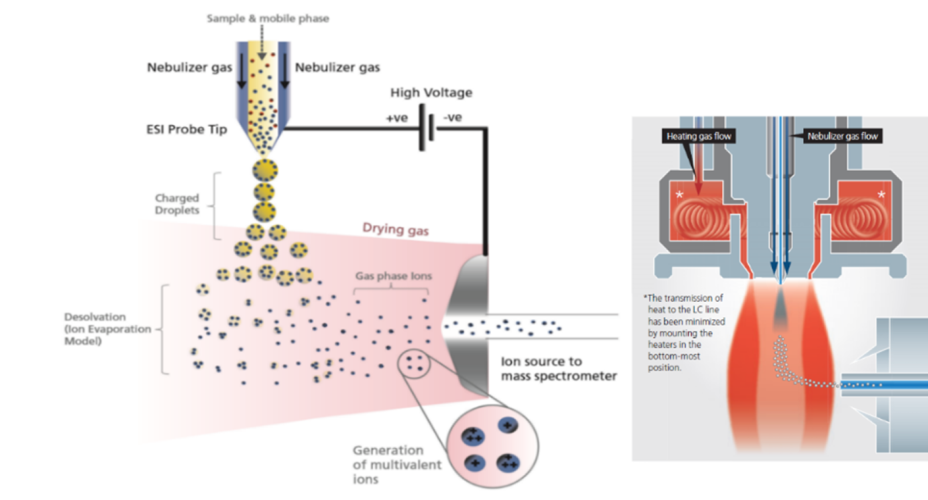

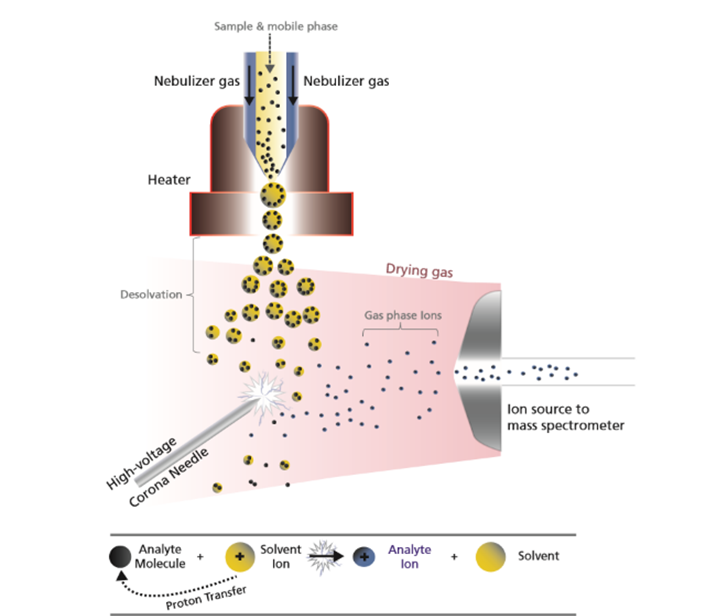

1. Ion Source

- Responsible for ionising and transferring analytes into the gas phase

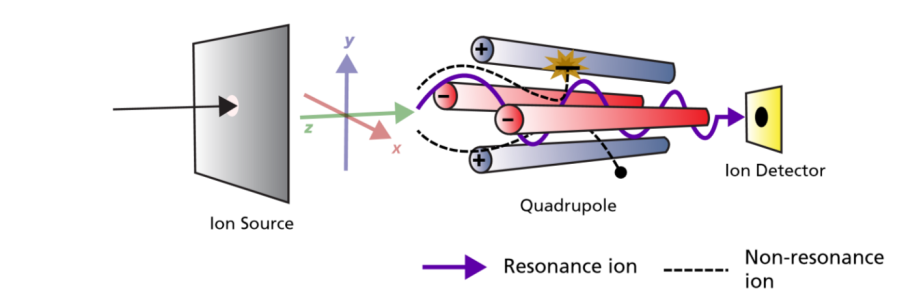

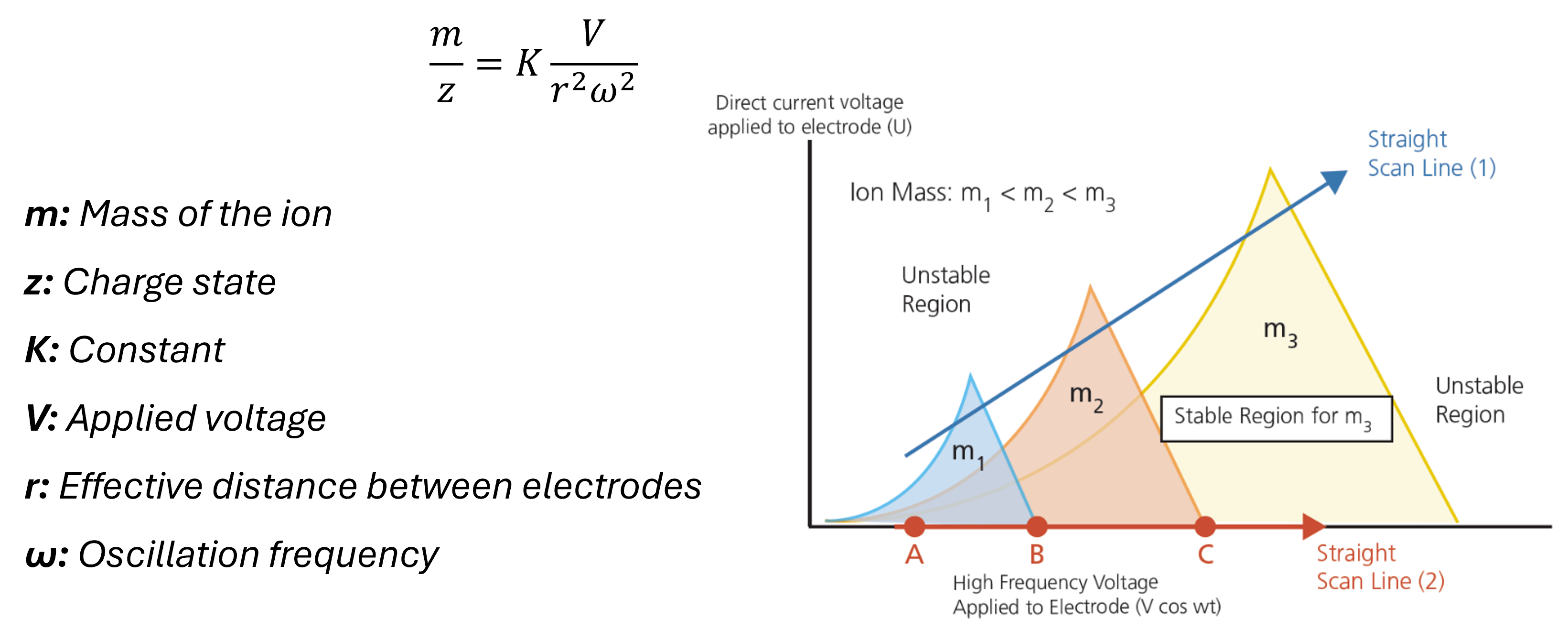

2. Analyser

- The core of the mass spectrometer, which separates ions based on their mass-to charge ratio (m/z)

3. Detector

- Captures the ions, amplifies the signals and transmits the data to a workstation for recording and analysis

Let's investigate each component in more detail:

Ion Sources:

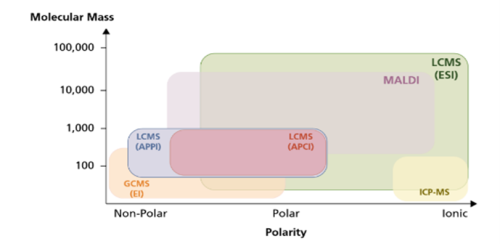

A variety of ionisation technologies are available which should be selected based on the properties of the analytes to be analysed. Key factors include polarity range, molecular size of analytes and sample complexity. Figure 1 gives an overview of typical ionisation techniques based on the polarity and molecular weight of the compounds. The most ubiquitously used technique is the electrospray ionisation (ESI) mode. Below we will examine the two most commonly used techniques.

Fig. 1 Overview of common ionisation techniques and areas of application

Analysers:

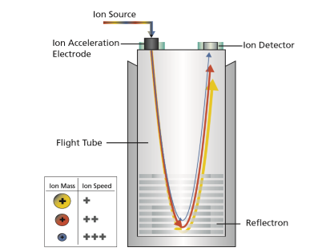

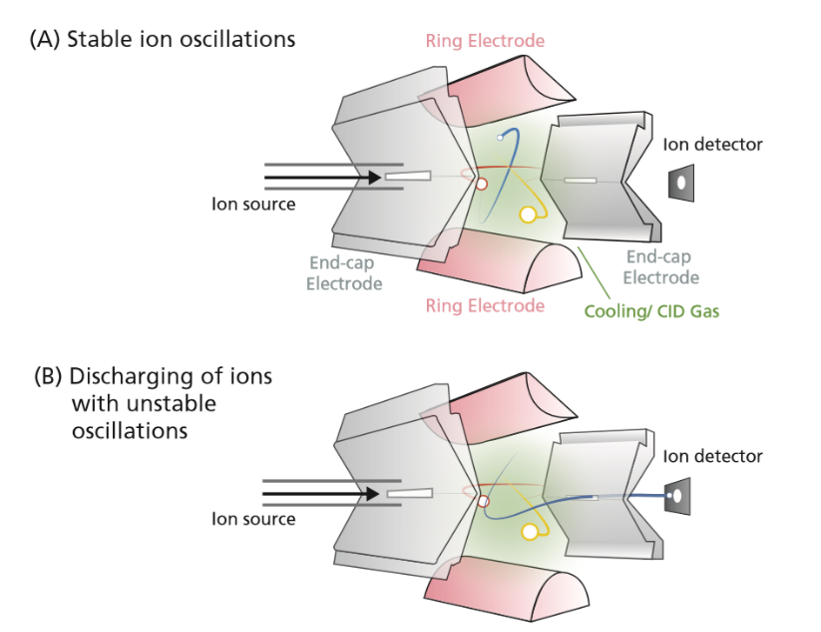

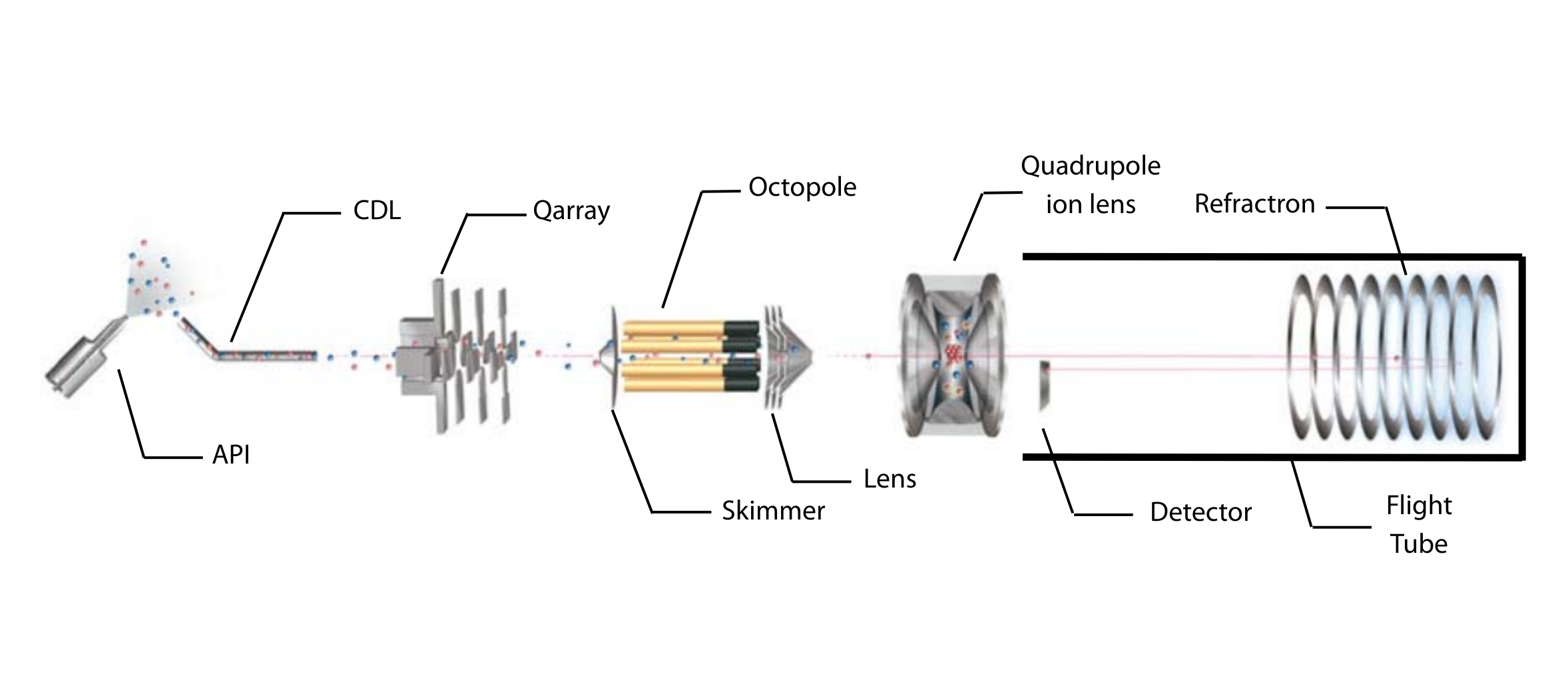

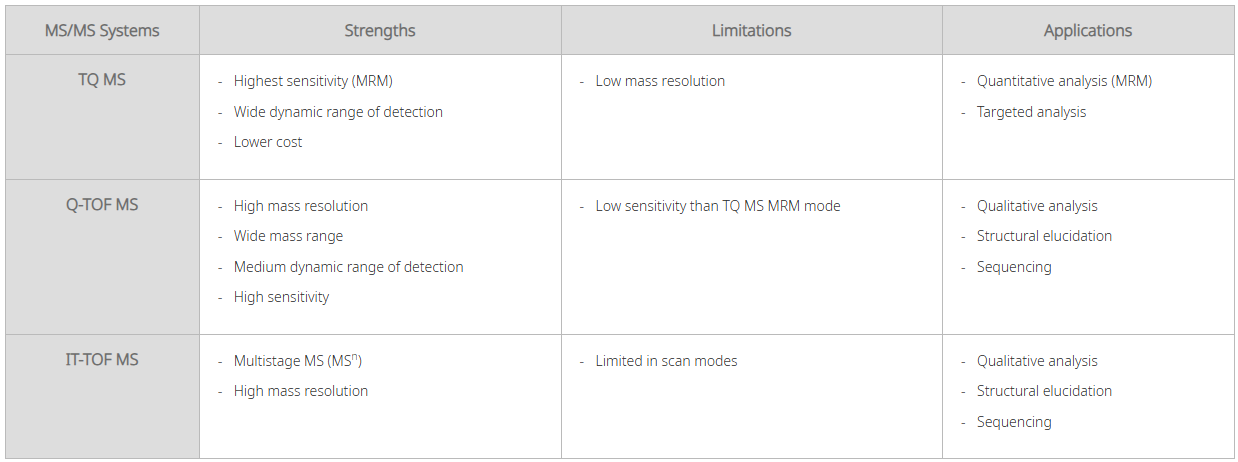

The mass analyser is one of the critical parts of the instrument which separates the ions. There are several types of mass analyser which all have different principles and mechanisms. Below are some of the most commonly employed.

Detectors:

Commonly used detectors in mass spectrometry include secondary electron multipliers and microchannel plates (MCP).

Secondary Electron Multiplier

Fig. 9 Schematic of an MS detector

Ions strike a conversion dynode, releasing electrons that are amplified into measurable signals (Figure 9). The ions are bombarded onto the conversion dynode to release a few electrons that are bombarded onto an alternating line of dynodes to increase the detection signal. These signals are displayed on the computer software.

In the next course unit, we’ll explore preventive measures for extending the lifespan of your LCMS and reducing potential problems.

Your Shimadzu LCMS Team

Related Resources

-

-

Watch short videos explaining analytical intelligence features of Shimadzu HPLC systems

-